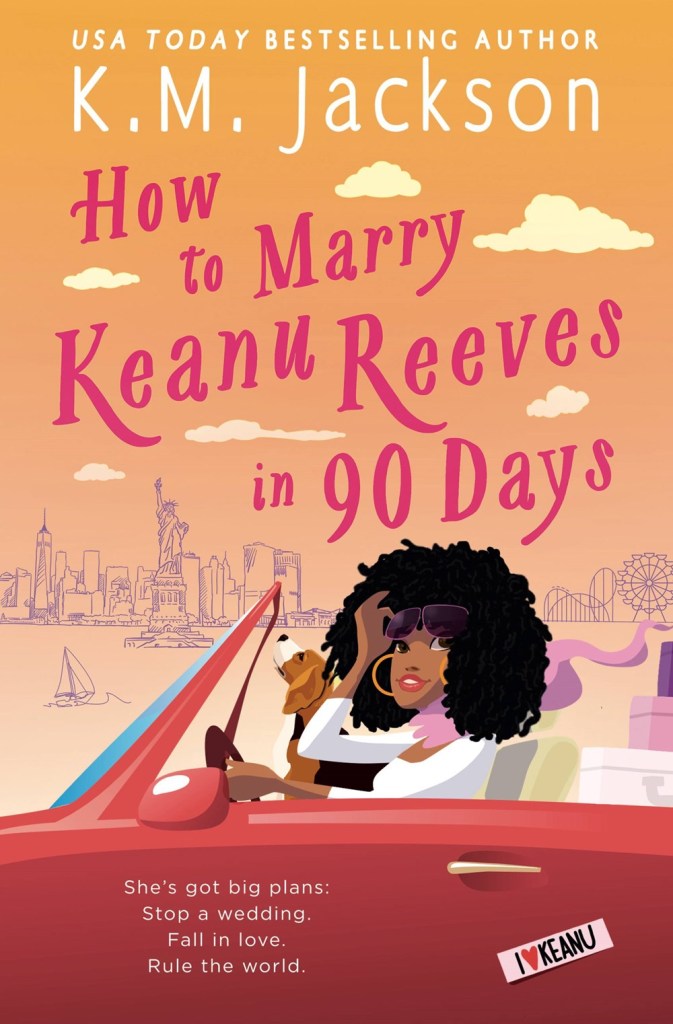

About the Book

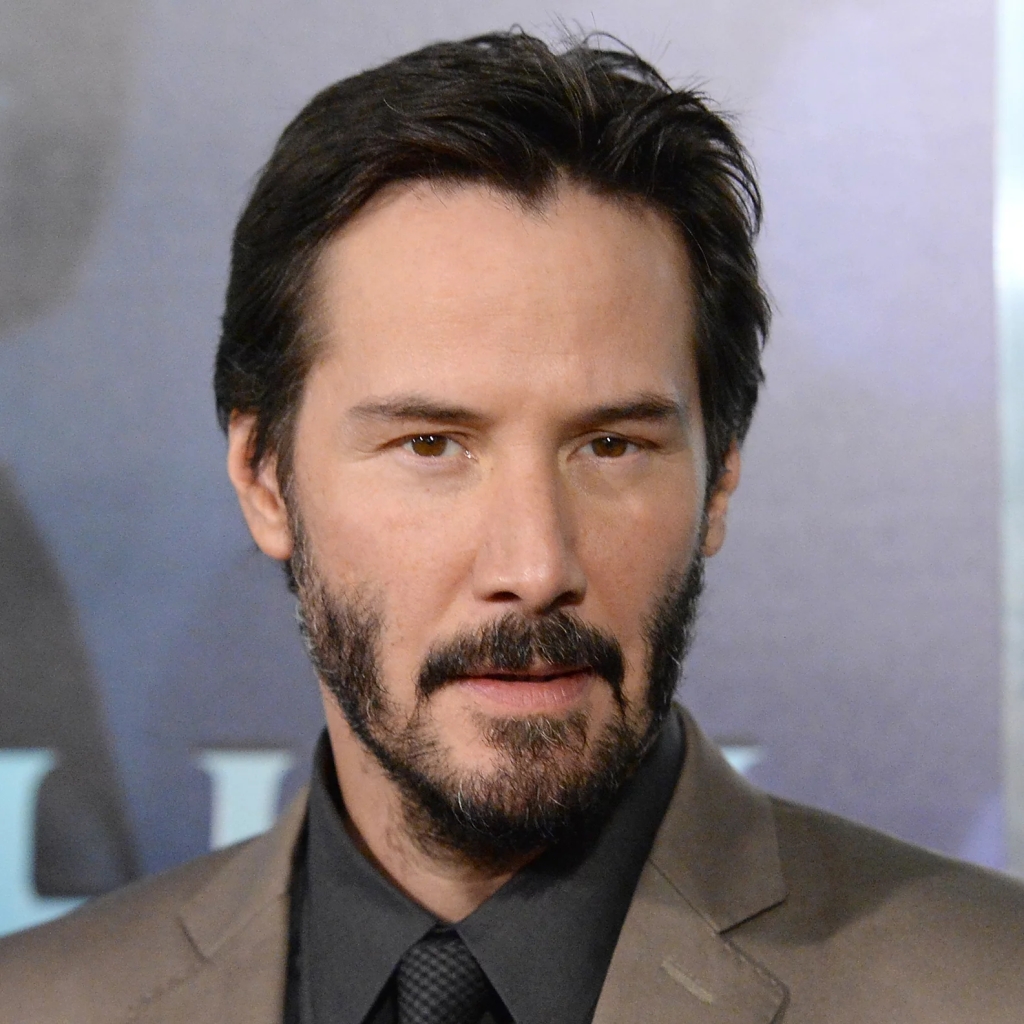

USA Today bestselling author K.M. Jackson delivers a hilarious road-trip rom-com perfect for fans of Meet Cute and When Harry Met Sally. Bethany Lu Carlisle is devastated when the tabloids report actor Keanu Reeves is about to tie the knot. What?! How could the world’s perfect boyfriend and forever bachelor, Keanu not realize that making a move like this could potentially be devastating to the equilibrium of…well…everything! Not to mention, he’s never come face to face with the person who could potentially be his true soulmate—her.

Desperate to convince Keanu to call off the wedding, Lu and her ride-or-die BFF Truman Erikson take a wild road trip to search for the elusive Keanu so that Lu can fulfill her dream of meeting her forever crush and confess her undying love. From New York to Los Angeles, Lu and True get into all sorts of sticky situations. Will Lu be able to find Keanu and convince him she’s the one for him? Or maybe she’ll discover true love has been by her side all along…

The Interview

Mrs. Jackson, I appreciate you speaking to me about your novel, How to Marry Keanu Reeves in 90 Days!

Your novel had me laughing out loud at the adventures you sent Bethany “Lu” Carlisle on in pursuit of the one and only Keanu Reeves.

Adira: How did you come up with the idea for How to Marry Keanu Reeves in 90 Days, and how did you decide who to include in your star-studded cast?

K.M. Jackson: Thank you so much for taking the time to interview me and read HOW TO MARRY KEANU! I came up with the idea of HOW TO MARRY KEANY REEVES IN 90 DAYS after seeing a tweet pre-pandemic that said the next Matrix and John Wick movies were set to come out on the same day (it has since changed due to the pandemic). I replied to the tweet saying, “Note to self don’t put out your next novel on Keanu day unless it’s that How To Marry Keanu Reeves In 90 Day’s Romance.” I got quite a lot of responses that said, “I’d read that,’ and from there a book was born.

A: What I appreciate about your female characters, Bethany Lu and Dawn, is that they don’t have life all figured out even at 40-years-old. You make it clear that they are still making mistakes, wrestling with imposter syndrome, and trying to decipher life when society tries to sell us all the message that you should have it all “together” by their age. What made you want to tackle this angle of “growing up” with your characters’ backstories?

KMJ: I felt strongly about wanting to make my heroine for this story over 40 and I wanted very much to make her feel real. To be honest I have gotten some feedback from some readers that she comes off as young because of the premise of the book and her obsession with Keanu, and the fact that she doesn’t have things all figured out at her age, to that I’d challenge folks to really look at themselves or the world around them honestly and ask who does have it all figured out?

I know I sure don’t. I’m older than both by characters, Lu and Dawn, and a mother and I am pretty hard on myself for not having all the answers. I often wonder and am frustrated by why I don’t have it all figured out by now. But I’m trying hard to give myself a bit more patience and grace.

A: Found or “chosen” family is a major part of your novel, thanks to Bethany Lu’s reliance on her best friends, Dawn and True, to help her with everything from her creative blocks to taking care of her mental health. Were you working from a specific definition of community when you developed these characters, and if so, how did it inform the development of your cast of characters?

KMJ: I wasn’t working from any specific definition of community when I came up with Lu’s friends but more from the friends that I felt would be the best support for her character and the story to make it what I felt it needed to be to be a romance that I would be satisfied with. Both True and Dawn are people I would be happy to know, share time with and most of all trust.

A: In the last year, we’ve all had to cope with one form of loss or another, and Bethany Lu’s choice of coping mechanism while entertaining to read touches on how traumatic and stagnant working through grief can make us. Why was it essential to show Bethany Lu working through the stages of her grief in How to Marry Keanu Reeves in 90 Days?

KMJ: Bethany Lu and in a way True working through their grief in HOW TO MARRY KEAU was essential for me because there needed to be something really strong to give Lu her initial Keanu hold and a major motivation to carry the story through. Also dealing with grief and loss was something that was heavy on my heart by the nature of when I was writing the novel. There was just no way I could get away from it so better for me to just lean in.

A: Bethany Lu’s character is dealing with a hot button topic that has come up a lot over the last year thanks to society’s reliance on social media and influencers to get us through the pandemic, which is the issue of parasocial relationships.

Bethany Lu’s plot to stop Keanu’s wedding to distract herself from her own troubles is something that many readers may find to be super relatable. Was there a particular message you were aiming to give readers about how we interact with celebrities and influencers online?

KMJ: Though Bethany’s obsession with Keanu does hold her up in some ways it’s also in ways a healthy coping mechanism. She’s still gone on with her life and has had quite a bit of success. Keanu has been her happy place and a bright and stable spot when things were not so bright and quite shaky. As for the interaction with Keanu, well thankfully there is True and Dawn to help her with keeping a watch on that. Though Lu is a smart woman she knows she really doesn’t stand a chance to get Keanu to marry her and she states this throughout the book. I was careful not to let her cross the line into stalker territory and keep her in the fan zone. I hope I did.

A: How to Marry Keanu Reeves in 90 Days was basically made to be adapted for film or tv! Are there any adaptions in the works? Or, are you working on something else that can tide us over until Hollywood comes a calling?

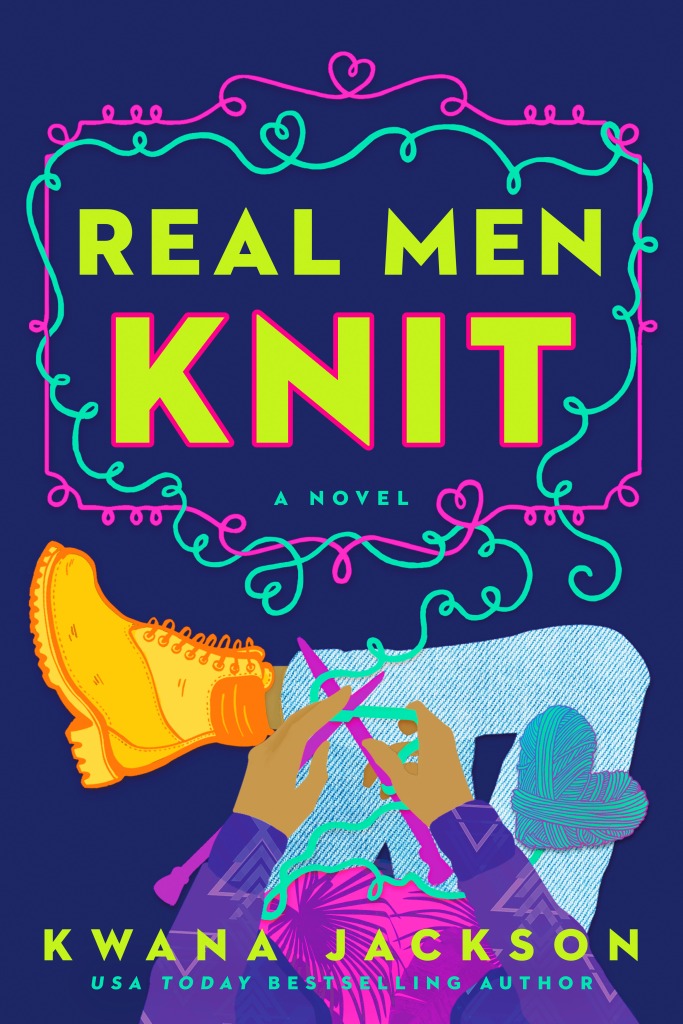

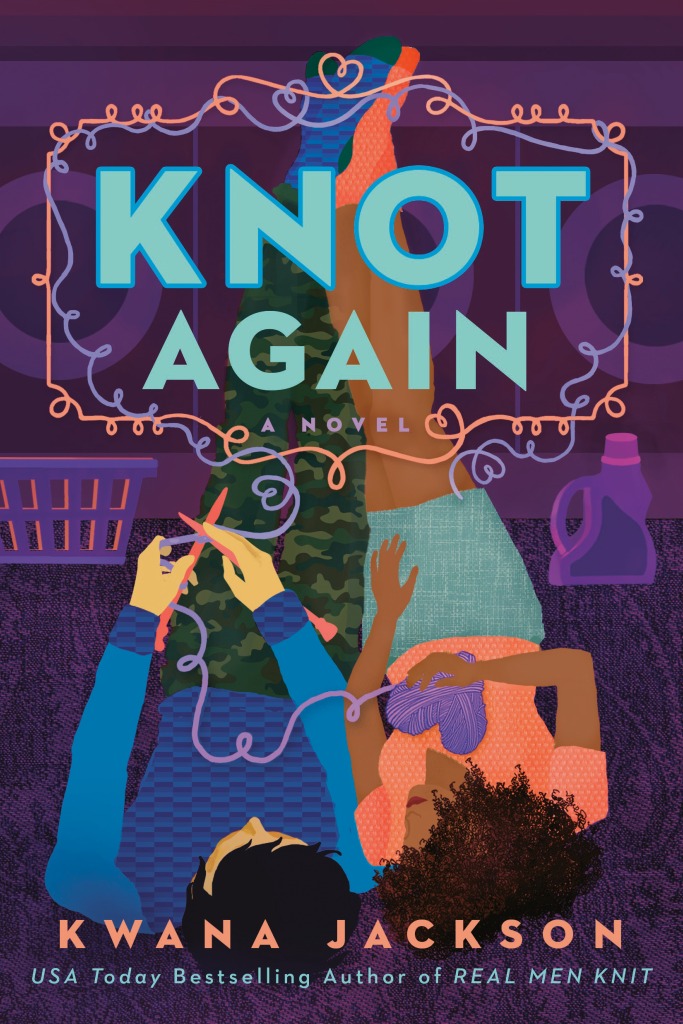

KMJ: Thank you so much for saying that about TV or film adaptations. I sure hope so. *cut to me saying a quick prayer and mentally crossing everything* No, so far adaptations are not in the works but who knows. And thank you for asking, I am always working on something. The next book in my REAL MEN KNIT series under my Kwana Jackson name comes out in July of 2022 and I’m currently thinking up what I’ll be writing next. I have a few ideas in mind. It’s been such a pleasure chatting with you!

About the Author

A native New Yorker, Kwana Jackson, who also writes as K.M. Jackson Jackson spent her formative years on the ‘A’ train where she had two dreams: 1) to be a fashion designer and 2) to be a writer. After spending over ten years designing women’s sportswear for various fashion houses this self-proclaimed former fashionista, took the leap of faith and decided to pursue her other dream of being a writer.

Now a USA Today Bestseller Kwana’s self-published novel, BOUNCE won the Golden Leaf for best novel with strong romance elements from the New Jersey chapter of Romance Writers of America. She was also named Author of the Year by the New York Chapter of Romance Writers of America and has been tapped by Oprah Magazine, ShondaLand and NPR for their Best Romance lists.

A mother of now young adult twins, Kwana currently lives in a suburb of New York with her husband.